OK, thanks to all who answered CASE#6 ‘Find the bleeding, stop the bleeding’

Plenty of good ideas, although some of the options are more realistic than others given the inevitable constraints of rurality. Glad that none followed the EMST mantra to the letter and killed him…

The setting of rural Australia poses a challenge, especially for those used to working in larger centres. James and Casey are used to this kind of stuff (although Casey’s mostly in-hospital and has even got a CT scanner…James is used to working out of a tent wearing just rabbit skins). Credit to Derek & Hildy for having a bash with spot on answers – but with kit we just don’t have!

You can read the case and initial comments here

Case discussions like these can be useful to reinforce what we already know and perhaps look at things from a new perspective. I chose this case to illustrate some FOAMed which can change the way rural doctors (mostly taught to EMST-ATLS standard only) can improve patient care. I will try to reference some of these as I walk though MY thoughts on this patient in a rural setting with FOAMed links.

Underpinning the approach in a rural location are four key tenets :

- Critical illness does NOT respect geography, so rural clinicians need to be prepared

- However they are constrained by relative infrequency of such cases, as well as potentially hampered by limited equipment and staff

- Concepts from prehospital & critical care are highly relevant to the rural clinician skill set

- FOAMed & Social Media can help disseminate these ideas and narrow the ‘knowledge translation’ gap from several years to almost zero

A few of us will showcase some of this at RMA2013 with the JAMIT series (just a minute medicine instant tutorials). Imagine being able to stream or access a downloaded 60 sec video file on how to perform a critical procedure – not a tool for novices, but a useful aide memoire for rural clinicians who may only do this stuff once in a blue moon. ACRRM have agreed to continue this, as the peak body for rural doctors in Australia…

Think that’s good? Then combine it with a tool like GoogleGlass to allow video streaming of key steps of a task to the proceduralist even as they gown and glove up before ‘cracking on’… that would be AWESOME!

Anyhow back to the trauma case

It’s not an unrealistic scenario – this sort of thing can and does happen in rural communities. As the local doctor/nurse/paramedic you will be called – data suggest over 53% of rural proceduralists have been involved in a prehospital incident in the previous 12 months in country Australia. Importantly the ambulance service in many rural areas will be staffed by volunteers – trained to Cert IV level but unable to cannulate, give drugs (other than penthrox/GTN) or intubate.

Let’s break the case down into little chunks.

First up – the ATLS/EMST way is useful as a structure for those who deal with trauma infrequently or as juniors. The skills learned on an ATLS-EMST course tend to be preserved for a few years, but the course content will lag behind current concepts – as will other courses of this ilk.

Before we even get to this patient, it’s worth stepping back. The visual confrontation of a man in pain with an obvious amputation and airway burns will induce a catecholamine surge in all but the psychopathic. Resist the temptation to rush in – ensure scene safety (get one of the Rotarians to turn off other gas sources and extinguish flames). Send for help – if you’re switched on, you’ll have brought your prehospital bag already. If not you’re going to have to use the ambulance resources and either bring extra kit to the scene or move the patient – without delay.

Consider the possibility of other injured patients. As the solo doctor you are a valuable resource and may be needed to attend to other injured patients. Think of how you will respond. In many rural communities the response will be

- untrained passersby / community first aiders

- volunteer paramedics

- career paramedics with extra skills

- rural doctors (some with airway skills, some not)

- small rural hospitals with limited capabilities, typically ED, some with OT

- retrieval services

- tertiary hospitals

This is no place for enthusiastic amateurs. Perhaps rural Australia could benefit from models utilising appropriately-trained clinicians like those used overseas? Could be useful to fill the void before retrieval services arrive…

So – check for danger – have a group huddle – allocate roles – then get control of yourself, team, environment…and then the patient(s). This takes 10-15 seconds. One can always learn from Cliff Reid on ‘making things happen‘.

Even as you survey the scene, you can see that his needs outstrip those of a small rural hospital. Allocate someone to activate ambulance, other clinical personnel, notify local hospital and give retrieval services a head’s up. Smart retrieval services have a presence in the Emergency Operations Centre and will be ‘on standby’ as the initial ambulance call comes through – a much more proactive approach than the usual sequence of calls from first responder-ambulance-local hospital-doctor-retrieval service.

OK – that’s the DRS part covered…now it’s ABCDE – isn’t it?

THIS IS CATASTROPHIC COMPRESSIBLE HAEMORRHAGE

The new paradigm is C-ABC. Direct pressure via a combat application tourniquet (or BP cuff locked in inflation) needs to be applied. Faffing about with a C-collar whilst he exsanguinates may be the ‘EMST way’ but won’t help him.

The combat application tourniquet is a broad strap, pulled tight then tighter still with a windlass and locked into position. The CAT I use has a space for marking the time applied. This will buy some time – but there is no doubt this chap needs surgery and you may have to make a decision as to whether this is a primary retrieval from the footy pitch or if there’s time to retreat to the local hospital (with OT capability) to tie off bleeders and manage as a secondary retrieval.

The CAT will hurt. Given his state (flailing around on the ground) you may decide to give him an slug of intramuscular ketamine to gain control of the patient and alleviate his pain. Dosing needs to be judicious – not enough to obtund him completely. Consider this as the first step with the possibility of loss of airway and need for an RSI.

Once done, transfer him to somewhere with 360 degree access, access to monitoring and protected from the elements – a trolley at the rear door of the ambulance may suffice, or even commandeer the local footy clubhouse. If close-by (our footy oval is 200m from the hospital) you may decide to transfer him to your own ‘shop’.

AIRWAY

Now – to the usual starting point.

You can make a good argument for early intubation. I’d raise here the concept of his ‘anticipated clinical course’ – he’s going to OT and has airway injury that will likely progress – so you might as well intubate on these grounds alone. Intubation for humanitarian reasons is also reasonable – he’ll be in pain and this is not the time to be faffing around with the ultrasound or nerve stimulator doing blocks!

How to intubate? FOAMed, highlights the following, not covered by EMST/ATLS

- Challenge-Response checklists as cognitive aid

- Kit dump

- Team brief on plans A-B-C-D and equipment to manage each

- NODESAT first-pass success with bougie, occipital pad, apnoeic diffusion oxygenation

- Induction with ketamine as ideal induction agent (don’t be a propofol assassin)

- Paralysis with rocuronium vs suxamethonium (awakening not an option)

- Lack of evidence for cricoid pressure

- Low threshold for surgical airway, scalpel-bougie-tube not needle cricothyrotomy

- Having a post-intubation plan prepared

Have a listen to Scott Weingart on tubing the shocked patient.

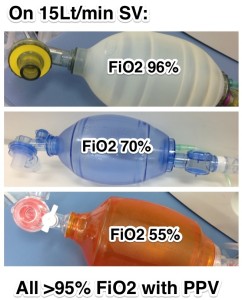

Our patient will need adequate pre-oxygenation with a bag-mask valve- be aware that not all bag-masks are the same! For the spontaneously breathing patient, there can be significant differences in FiO2.

You may decide to add a PEEP valve if available – this will compensate for deficiencies in the bag and any hypoventilation, espec in this (ahem) larger-sized bank manager.

Supplemental nasal oxygen is a must, along with usual BMV preoxygenation – but may require extra O2 cylinders. Use this to both increase the FiO2 when using a BMV and to allow passive apnoeic diffusion oxygenation during intubation. New concept? Oh dear – read more here.

You’ve already given a judicious aliquot of IM ketamine to gain control of him and as analgesia prior to establishing IO or IV access. Now’s the time to use ketamine as the ideal induction agent for the hypotensive trauma patient. A standard dose 2mg/kg propofol will kill him as surely as executing by lethal injection.

As Casey mentioned, this is a one-way airway plan – DL-iLMA-Cut neck is my algorithm so giving 1.6mg/kg of rocuronium for paralysis will give optimal intubating conditions with same onset as suxamethonium. Waking him up if fail to secure airway is not an option.

Your ETT can be preloaded on the bougie with a Kiwi- or Pistol-grip to avoid the weight of the ETT causing loss of bougie tip-control. I find pre-loading avoids embarassing ‘hang up’ on the ET connector. Speaking of hang-up, you may need to use a ‘flip-flop’ manouevre to pass ET into the glottic opening.

Of course intubation needs to be first pass success with no hypoxia or hypotension. Watch this video for a demonstration.

Cricoid pressure is standard teaching, but may actually hamper your view. The French don’t use it and it may be hard to give correctly with untrained assistants.

This chap is going to ride the oxy-haemo-coaster all the way down unless you apply meticulous technique.

One can argue about prehospital anaesthesia & intubation in the field vs intubation back in the relative safety of either ED or OT. The decision to scoop and run vs stay and play will be governed by many factors – no protocol or ‘one size fits all’ will answer this. Make a decision based on your own skills, available equipment and the assistance you will receive.

Even if you are a shit-hot intubator, I guarantee that you may struggle doing RSI on the ground, under the hot Australian sun (making laryngoscopy difficult), with untrained assistants. Even harder for the ‘occasional intubator’ not trained in the demands of prehospital medicine. Its going to be a balance between time and need to secure his airway. Occasional intubators (most rural doctors ) should listen to these two podcasts (Minh & Rob podcast 1 & 2)

Before intubating you may need to gather a quick history (knowing he’s on dabigatran would be useful), determine the GCS and establish that there’s no sensory level. There’s often inter-observer variability in recording the GCS – using a cognitive aid and recording best response is key. Beware sternal rub as a painful stimulus – localising to pain and abnormal flexion can be confused. I use a trapezius squeeze from the head end; this also encourages me to look in eyes & talk to my patient. It’s also ideal for applying in-line immobilisation if needed. Some (and I am one) would argue that the GCS is functionally irrelevant – check out this paper. If you must use it, at least know how to!

In order to intubate you’ll need IV or IO access. I’m always bitching about the local Bone Injection Gun, with high failure rates locally despite staff training. This is of course anecdote – but there are papers to suggest EZ-IO as the better technique. Personally I think this is because of greater tactile feedback and the fact that we DO at least practice with this device on many of the usual “alphabet soup” courses such as ATLS-APLS-ELS.

Once the tube is in, secure it – use a tie not tape, but don’t tie too tight! Keep him adequately sedated. Use the appropriate pre-determined ventilator settings. In the field you may have a fire or ambulance volunteer tasked to this – make sure they don’t hyper- or hypoventilate him…or worse still, pull out the tube.

In ATLS-EMST we teach “airway with cervical spine protection”. Does he REALLY need a cervical collar? Have a listen to Alex Tzannes from GSA-HEMS on this. An occipital pad may be all that is needed and in fact give a more ‘anatomical’ position.

BREATHING

Next on our usual trauma mantra is B for breathing. You need to quickly look for haemothorax tension pneumothorax and flail. May need PEEP to aid ventilation – a simple PEEP valve added to the standard Laedral bag-mask-valve may help, or set ventilator settings accordingly.

A sudden decline in BP or raised airway pressures in the ventilated patient should alert you to possibility of a tension pneumothorax. A needle decompression won’t cut it. In ventilated patients, be familiar with the technique of finger thoracostomy.

CIRCULATION

Finally onto circulation. If you had followed the usual ABC approach he’d be dead by now. Sure he’s got a traumatic amputation – your tourniquet has arrested the bleeding, but there may well be more blood loss. Think ‘blood on the floor and four places more’ – head – thorax – abdomen & pelvis – long bones.

Belly needs to be evaluated for bleeding – there was initial concern re; LUQ pain – perhaps a splenic injury? Wrap the pelvis – use a proper binder if there is ANY concern re: a pelvic injury. Pull straight any fractures & splint them. Remember to apply splints to skin!

Other tricks might include use of

- haemostatic dressings,

- foley catheter to tamponade bleeds (useful with those glass shards in his neck),

- tranexamic acid for ongoing blood loss/internal bleed. Give a gram within the first hour. It’s cheap as chips, NNT of around 60 in CRASH-2 although subgroup analysis suggests NNT of ~ 40 if given early.

The confounder here is that he’s on dabigatran – unlike warfarin you cannot reverse this. In fact we don’t really know how to. Why’s he anticoagulated? For non-valvular atrial fibrillation – so he’s probably also beta-blocked – all of which will affect his haemodynamic response to blood loss. So for now we need to consider fluid resus before getting freaky with fancy blood products.

Even EMST-ATLS has (at last) moved away from the old mantra of “two litres of crystalloid, stat”. Flooding him with crystalloid is going to dilute his clotting factors, make him hypothermic and potentially worsen outcomes.

Remember “the best clot is the one you’ve got” – don’t dislodge it! I would give 250ml boluses of crystalloid, titrated to radial pulse – if any fluids at all.

Whilst we’ve ‘re-discovered’ balanced resuscitation (first described by Cannon back after WWI), there remains some limited controversy – listen to this 2013 take from Simon Carley at St. Emlyns on the PROMMT data.

Of course any fluids given should be warmed to help avoid the lethal triad – acidosis, coagulopathy and hypothermia. Locally we use the en-flow system, which is effective but requires AC power from a mains socket – something for use in OT or ED.

So by now we should be moving him from the footy pitch to the local hospital, given that retrieval services are busy elsewhere and unlikely to arrive for some hours. Like it or not, his current care remains within the limited capabilities of a rural hospital until he can be moved out.

If IV access is insufficient, I might need to place a rapid infuser catheter – converting whatever standard IV I have into a 7Fr hosepipe. Again there’s a danger of ‘flooding’ him with fluids which may worsen bleeding. Aim for a MAP of 70, don’t get too focussed on “normalising blood pressure”. He may need large amounts of fluid down the track as part of his burns management – we’ll calculate this a bit later.

ATLS-EMST teaches us to send for “urgent cross match” when establishing an IV. Where I work it will take over 24 hours to get blood results, let alone a cross-match (one of the drawbacks of living on an Island). However we can use a bedside iStat point-of-care device to measure simple parameters – INR, glucose, Na/K, Creat, Lactate and gases. I would be interested in these, but they’re not essential.

It’d be lovely to have ROTEM/TEGS, and access to fancy blood products – in rural areas our choices are going to be O negative blood (maximum of 2-3 units in most hospitals) or hope retrieval can bring some blood with them. We have cryoprecipitate and I might use this – although to be honest I don’t think it’ll help that much with his dabigatran! Seems not much does, other than time.

There are well-established protocols for massive transfusion, with most moving towards 1:1:1 ratios of packed cells:platelets:FFP – but again these are not available in many rural hospitals. Casey was too modest to mention his approach to massive bleeding in Broome, so here it is

We know that whole blood is the ideal fluid to transfuse – so in dire circumstances one might consider whole blood from a ‘walking blood bank’ or even a simple auto-transfusion technique. For this, use a sterile plastic container, inverted and connected to IV tubing. Cut the container in half, then place gauze soaked with patients own blood into the inverted bottle – blood will trickle down into the IV and back to patient. Not my preferred approach, but “if needs must”.

As always the best solution is to “find the bleeding, stop the bleeding”. In this case, retrieval are some hours away. I’d want the theatre team to be setting up whilst we move him from footy pitch to hospital, then take him to theatre along with rural proceduralist colleagues and attempt repair of obvious bleeding. Now is the time to let down the tourniquet and tie off any bleeders & use haemostats.

As to whether you open the abdomen for his ongoing intra-abdominal haemorrhage? This is tiger territory for most of us – many rural GPs will do Caesarean sections and as such are also trained to do an emergency hysterectomy..but a splenectomy might be pushing it. Often those who trained In South Africa or whom are involved with organisations like the AAD may have received training in ‘damage control surgery’. Now’s the time to see if they can apply it..

A “PanScan” is not an option – the nearest CT scanner is in the capital city. Ultrasound can be useful – I am a fan of the SUSS-IT examination (seconary ultrasonographic survey in trauma).

He may be bleeding from wounds posteriorly and a log-roll will be needed if not already performed. This is a great opportunity to remove clothing, apply burns dressings and estimate surface area of burns. Keep him warm and covered. As others have suggested, antibiotics and ADT would be needed. Check his pupils – any signs of head injury or subdural from flying debris? Although we usually tape the eyes, you may need to re-evaluate pupils as he is transferred. But beware causing damage to his fragile corneas as he is moved.

Other considerations?

We have already talked about scoring the GCS prior to intubation – post-ETT his verbal response will be scored as a ‘T” – so the fully anaesthetised patient would be recorded as M1VTE1. I’d want to keep him adequately sedated and I have the luxury of maintaining him on inhalational anaesthetic once back in my small rural hospital awaiting the retrieval team.

There is a real danger of clinical inertia or a therapeutic vacuum, particularly after key stages such as intubation, chest drain placement or log roll. An ideal resuscitation would allow parallel processing with a designated team leader and teams devoted to various tasks.

Upstream and downstream communication between team members would be vital and preferably the team would have trained together using simulation. This is one benefit of rural teams – we know each other by name, know each others strengths and weaknesses. However there may be a tendency for both decision-making and performance of procedures to be ‘doctor only’ tasks – which forces sequential not parallel processing of tasks.

Co-opting ancillary staff such as ambulance and fire volunteers, clerical staff or even family members as extra pairs of hands may be needed. Control of non-essential personnel, particularly anxious friends & family members or the media will be required.

The resus room or theatre should be well-lit, allow 360 degree access to the patient, and be warmed. Relevant protocols for clinical management and drug infusions should be readily available and ideally common between rural hospital and retrieval service. Monitors should be visible to the team leader and should include :

- SpO2

- ETCO2

- Anaesthetic gases

- NIBP

- Pulse, ECG

- Temperature

I’d place an arterial line, NGT & IDC once in the ED or OT.

The ATLS-EMST mantra of constant re-evaluation will be useful here and should be used if there is any change in condition. Otherwise continue with a top-to-toe examination looking for other injuries and prepare the patient for transfer.

Moving him from the ground to ambulance stretcher to ED or OT bed is fraught with danger – this is when lines can get pulled out, ETT dislodged. I am not a fan of the 1-2-3 approach to lifting, rolling or moving patients. If you’ve ever seen Lethal Weapon 2 and the infamous “bomb on the toilet” scene you’ll know what I mean. I use a ‘ready-brace-lift’ or ‘ready-brace-roll’ method after appropriate brief. No ambiguity with that approach.

Once the retrieval team arrive?

One often sees clinicians NOT LISTENING at patient transfer – instead there’s a mad rush to check BP, pulse, ventilator settings. Fair enough if the patient is dying in front of you, but if not it takes perhaps 45s to give a structured handover. Everyone (not just team leader) needs to STFU and listen or else vital information will be lost. I sometimes have to ‘body block’ the retrieval team – thankfully ninja-trained RNs with significant netball blocking experience help…

I always use a structured MIST summary and transfer checklist – not just ABCDE but all the way down to …KLMNO !

Here’s a summary of the patient for handover to retrieval:

TRANSFER SUMMARY

Mechanism – 54 yo man involved in a blast injury

Injuries – Traumatic amputation of right lower leg and on dabigatran for AF. Airway compromised by burns. Sore belly with possible splenic injury.

Signs – RR 26 BP 80 p 120

Treatment – ETT on scene for airway protection, anticipated course & humanitarian reasons. Combat application tourniquet applied to wound. Minimal volume resus to MAP 70. Transported to local hospital for ongoing care pending secondary retrieval.

IN DETAIL, A-O handover (written)

A Airway patent & protected with size 8.5 ET 22cm at incisors, midline.

Grade II view Mac 3 blade DL but developing supraglottic odema from airway burns

B TV 500 RR 10 PEEP 5 ETCO2 35

No evidence PTX/HTX on sonographic exam

C p90 BP 100 initial lactate 1.9 INR 1.2 likely ACOTS

Bleeding from

– R lower leg traumatic amputation, CAT applied 13:37pm

- numerous glass shards upper thorax, haemostatic dressign applied

- Tender in LUQ, possible splenic injury, given TXA 1g load

- Taken to OT and abdomen packed. All available O neg used.

- Possible pelvic injury, pelvic binder to skin

D Initial GCS XXX, now M1VTE1

E glass shards in neck, haemostatic dressings applied

F received 500ml crystalloid prehospital to MAP 70 then three units PRCs

Considered walking donors but as stable elect to wait for retrieval team

G last ate 13:00, NGT placed post intubation

H Hb 122. INR 1.2. On dabigatran. Lactate now 1.3. Glucose 4.8

I Infusion of propofol for transfer sedation ready, currently on sevo inhalation Mac 1.1

J JVP not visible. SUSSIT indicates under-filled, intra-abdominal free fluid

K Temp 36.2 with Bair hugger, fluid warming

L 18G R ACF, 14G L forearm, R radial art line

M received ADT and 1g cefazolin for traumatic amputation

N Notes complete and NOK contact details

O Other – he’s privately insured but will go public for today’s transfer

Anything else?

Reblogged this on PHARM.

Great work

One small point

Re:

“You may decide to add a PEEP valve if available – this will compensate for deficiencies in the bag and any hypoventilation, espec in this (ahem) larger-sized bank manager.”

Worth clarifying that adding a PEEP valve may improve oxygenation but will not address the FiO2 shortcoming of using a BVM in a spontaneously breathing patient – they still need to generate negative inspiratory pressure to open the inspiratory valve. This can be overcome by giving ‘assists’ with the bag as the patient breathes in – but runs the risk of gastric insufflation.

I’ve also summarised all the pitfalls of GCS here if you’re interested:

http://lifeinthefastlane.com/education/ccc/glasgow-coma-scale-gcs/

Chris

Quite informative piece of article

Newton @Kenyatta University School of medicine